2 Creativity and Recognition

The

second topic was discussed through a hypothetical scenario, which the organizing

team believed would touch all participants in one way or another:

THE CHARANGO PLAYER OF SUCRE

A young man, who had lived all his life in Sucre,

instead of appreciating foreign music like hip hop, rock, or cumbia, had learnt

to love the music of his forebears. He learnt to play the charango in the style

of his grandparents’ community, a place called Juchuy Mayu in Northern Potosí. He

was very proud to play this music, and felt happy when he shared it with

audiences in his performances and recordings. He began to acquire considerable

popularity as a charango player, enabling him to produce his own music DVDs.

One of these, entitled Juchuy Mayumanta (‘From

Juchuy Mayu’), consisted entirely of songs inspired by melodies from this community,

although modified by him. The young man registered all these compositions under

his name with SOBODAYCOM. The video, filmed in the countryside around Sucre,

used a variety of images to evoke a romanticised and idealised rural life. By the

age of 30 he had become a well-known musician, but nonetheless remained very

poor. He lived in a small flat, paid for with a loan (anticrético), and dreamt of one day owning his own house. In his

home he had installed a small digital studio with which he could record himself

and acquire a little additional income by recording other musicians.

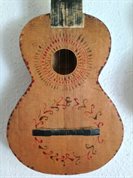

Rural-style

charango from Northern Potosi - Photo credit: Henry Stobart

The

following questions were posed and participants reflected on them in mixed

groups:

a.

How would you feel about this scenario if you

were:

·

the young man?

·

the audience for the musical group?

·

a member of the community of Juchuy

Mayu?

b.

What do you think about the young man

registering the compositions in his own name?

c.

What forms of recognition can we identify in

this example?

Ramón Caizari Coca and Zandra Loayza Pereira - Photo credit: Phoebe Smolin

Discussion

Participants expressed both negative and positive

ideas about this story, reflecting on how all of us borrow or appropriate

elements from other cultures and expressions. For example, foreign researchers

teach Bolivian music abroad; Bolivians incorporate indigenous music in national

expressions that transcend the country’s borders, etc.

The participants’ answers often reflected a certain ambivalence. They recognized, on the one hand, the tenacity of the young charango player and his passion for the music of his grandparents. On the other hand, they criticized him because he had not given more explicit recognition to the music’s community of origin. Yet, the issue of origins also proved to be complex. When one lives in and learns to play music within a community, one usually does not learn everything from a single person. For example, participants asked: “Who teaches us to play music for funerals?” “To whom does the knowledge of different charango tunings belong?” Some people expressed a protectionist approach to indigenous or originariomusic, making an appeal for people to study, record, and regulate its subsequent use. For some participants, the young charango player should have focused on playing music only in its original form. Others voiced the importance of a cultural dynamism that develops through a dialogue between generations. Thus, appropriations that look back allow our gaze to look forward in a dynamic way, enabling some music to achieve visibility in contexts where it would not otherwise be recognized.

Waldo Papu - Photo credit: Henry Stobart

Participants also pointed out that the dialogue between young people and elders takes place without considering the other half of the human population: daughters, mothers and grandmothers. What is more, elements of nature and supernatural beings are often left aside, even though, among many cultures, these are identified as key sources of sounds and creativity. Some participants voiced criticism of the examples utilized in the workshop, because they tended to focus only on music, a field dominated by masculine roles. They suggested that in order to better recognize women’s creativity, other creative fields where women are more present should be included.

Participants also pointed out that the dialogue between young people and elders takes place without considering the other half of the human population: daughters, mothers and grandmothers. What is more, elements of nature and supernatural beings are often left aside, even though, among many cultures, these are identified as key sources of sounds and creativity. Some participants voiced criticism of the examples utilized in the workshop, because they tended to focus only on music, a field dominated by masculine roles. They suggested that in order to better recognize women’s creativity, other creative fields where women are more present should be included.

Others reminded the workshop that this kind of analysis must consider the fundamental fact that those who enjoy the benefits of cultural products--whether these are textiles, music, dance, or poetry—exist in distinctly sexed bodies, and gendered roles; values are historically determined, in one way or another, by the differences between what is expected of men and what is expected of women.

Rainy season kitarra - Photo credit: Henry Stobart

Various forms of recognition were mentioned, including moral recognition. While some participants said that all creative work must be compensated, others differentiated many kinds of remuneration that ranged from barter to other forms of reciprocal cooperation, such as the Andean aynior the Chiquitos minga.Even if some creators manage to make a living, perhaps for example, working within an institution, it was noted that they still hoped for some sort of recognition of their creative work, even if it were only symbolic. Some mentioned that institutions, such as SOBODAYCOM, also generate forms of recognition, but that this institution operates on the basis of copyrights granted to individuals. Collective rights do not fit within its framework. Moreover, many peoples and collectivities, as in the case of the many people who dance and play music in the popular festival of el Señor del Gran Poder, are not registered with SOBODAYCOM. Participants stated that it is not right for one individual to receive all the recognition when that person’s inspiration still comes from the community as a whole. Moreover, the terms “author” and “community” were contested. It was also suggested that a debate on the laws and regulations governing these issues should not substitute for on-going dialogues among peoples.

Various forms of recognition were mentioned, including moral recognition. While some participants said that all creative work must be compensated, others differentiated many kinds of remuneration that ranged from barter to other forms of reciprocal cooperation, such as the Andean aynior the Chiquitos minga.Even if some creators manage to make a living, perhaps for example, working within an institution, it was noted that they still hoped for some sort of recognition of their creative work, even if it were only symbolic. Some mentioned that institutions, such as SOBODAYCOM, also generate forms of recognition, but that this institution operates on the basis of copyrights granted to individuals. Collective rights do not fit within its framework. Moreover, many peoples and collectivities, as in the case of the many people who dance and play music in the popular festival of el Señor del Gran Poder, are not registered with SOBODAYCOM. Participants stated that it is not right for one individual to receive all the recognition when that person’s inspiration still comes from the community as a whole. Moreover, the terms “author” and “community” were contested. It was also suggested that a debate on the laws and regulations governing these issues should not substitute for on-going dialogues among peoples.

Jacha Marka tarka ensemble (Oruro) performing in Condo - Photo credit: Henry Stobart

Participants mentioned the need to emphasize that mutual respect can exist among communities, with or without the presence of business concerns, market competition, or the law. To illustrate this, one participant told the story of a group from Tiwanaku that played for the dance procession of el Señor del Gran Poder; those from Tiwanaku played their music next to others playing different musics. Mutual respect existed among the groups, despite the fact that competition continued to shape the dynamics.

Participants mentioned the need to emphasize that mutual respect can exist among communities, with or without the presence of business concerns, market competition, or the law. To illustrate this, one participant told the story of a group from Tiwanaku that played for the dance procession of el Señor del Gran Poder; those from Tiwanaku played their music next to others playing different musics. Mutual respect existed among the groups, despite the fact that competition continued to shape the dynamics.

Some participants proposed that the young charango player in the fictional story needed more education about cultural respect. He could have shown this by specifying details about his grandparents' community and by asking community permission to use these materials. Such permission, it was said, did not operate in a vertical fashion. This led workshop members to share examples of requesting permission to record or conduct research. Some communities refused to grant permissions while others had granted it happily. Thus, others questions were posed: Who should be recognized? And what form should this recognition take?

On the same topic, at least one participant even suggested that promotion and dissemination through tourism could result in a broader circulation of local music, and that this might be a form of recognition, given the possible economic advantages that could ensue.

Juan Carlos Cordero - Photo credit: Henry Stobart

These questions opened up a new subject: the effects of the market on music and its production. People stated that music belongs in a whole web of social relations, but that when it enters the market, it becomes a commodity; in this process, one must be aware of all the transformations that accompany this disconnection from meaningful social contexts. Some participants spoke of the need to think about creative endeavours in relationship to bridges--between rural and urban spheres, between the community and the individual, and between internal and external dimensions.

These questions opened up a new subject: the effects of the market on music and its production. People stated that music belongs in a whole web of social relations, but that when it enters the market, it becomes a commodity; in this process, one must be aware of all the transformations that accompany this disconnection from meaningful social contexts. Some participants spoke of the need to think about creative endeavours in relationship to bridges--between rural and urban spheres, between the community and the individual, and between internal and external dimensions.

Others flagged the problems of applying these dichotomies at the moment of analysis, emphasizing that the collective and the individual stand in a continuum; one always belongs to a community, and in these contexts the collective is a continuation of the individual.

People also asked where the limits of a community could be drawn, given Bolivia’s high levels of migration. Urban cultural expressions have long been found in rural areas, just as today many indigenous people live in cities. People asked: what happens when music moves from a ritual context to the market and to the realm of art? For many participants, immersion in a world market poses many problems, making it necessary to develop more mechanisms that better promote protection and/or respect towards others’ cultures.

Waka waka dancers during the Entrada Universitaria, La Paz - Photo credit: Henry Stobart

The organizers made certain interventions,

presenting a case about Lomerío musicians who insisted on formal recognition of

their music; a case in which the communities of Yura opted for collective

recognition in a cassette production of their music; and a case of Creative

Commons in which a model developed in the United States was transformed for the

context of Brazil (see the case studies and glossary for details).

Rethinking Creativity, Recognition and Indigenous Heritage by https://www.royalholloway.ac.uk/boliviamusicip/home.aspx is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://www.royalholloway.ac.uk/boliviamusicip/home.aspx